Thurman and the Missionary Mind

In 1935, Howard Thurman (far left) led a delegation to India to visit Gandhi.

Kendall Dooley is a community development practitioner, scholar, and co-founder of BLK South, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reclaiming and revitalizing historic Black neighborhoods in the South. With a background in Criminal Justice and Missional Theology, Kendall brings a deep commitment to improving the quality of life in under-resourced communities through holistic development, cultural preservation, and creative place-making. His work is shaped by his passion for justice, Black history, and fostering spaces where communities can flourish on their own terms. Learn More

When I first began ministry in an under-resourced neighborhood in Phoenix, Arizona, I raised financial support by calling myself an urban missionary. The language worked well when visiting churches or writing fundraising letters—it carried familiarity and evoked compassion. But one evening, a student asked me, “What do you mean by missionary?” He went on to say that missionaries were “white people who colonized and imposed their ideas on others.” His honesty stopped me cold. That conversation opened a deeper inquiry: Can the word missionary still carry moral integrity, or has it outlived its usefulness?

In the Advanced Philosophy and Ethics course I’m currently taking, I revisited this question through Howard Thurman’s reflections on his 1935 pilgrimage to India. Thurman recounts that everywhere his delegation went, Indian students asked, “Why are you here, if you are not the tools of the Europeans, the white people?” They pressed further: If Christianity is not powerless, why is it not changing life in your country? For Thurman, these questions exposed what he called “a definite problem to the missionary, particularly the American missionary.”¹

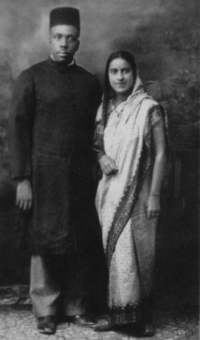

Howard Thurman and his wife Sue Bailey Thurman in India in 1936. Courtesy: Public Domain

To unpack this, I turned to philosopher Stanley Cavell’s Must We Mean What We Say? Cavell argues that our words gain meaning through shared use—the “must” of linguistic norms, the “we” of communal belonging, and the “mean” of moral responsibility.² Applying Cavell’s lens, Thurman’s account reveals a profound tension: the American missionary represents a Christianity that has failed to embody the justice and fellowship it proclaims.

Thurman later addressed this problem directly in Jesus and the Disinherited, where he replaced the term Christianity with the “religion of Jesus.” He reframed faith not as imperial conquest but as a love-ethic rooted in solidarity with “those whose backs are against the wall.”³ For Thurman, American Christianity had “betrayed the religion of Jesus almost beyond redemption.”⁴ His shift in language was both moral and theological—a move from domination to dignity.

As someone who once wore the label missionary, I now see how language shapes witness. The word itself has historically been used in relation to imperial practices such as colonization. Yet, through Cavell, we see that Thurman invites us not to discard language carelessly but to use it responsibly—to mean what we say. His example challenges all who claim to represent faith in public life to examine whether our words still serve life, or if they, too, have become powerless.

Reflection Questions:

What does Thurman’s view of the word “missionary” teach us about how we live out our faith?

How can the words we use to describe our faith better reflect what we truly believe?

R E C O M M E N D E D R E A D I N G

Notes

Howard Thurman, With Head and Heart: The Autobiography of Howard Thurman (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979), 126–127.

Stanley Cavell, “Must We Mean What We Say?,” in Must We Mean What We Say?: A Book of Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 1–43.

Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), 11.

Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited, 88.